|

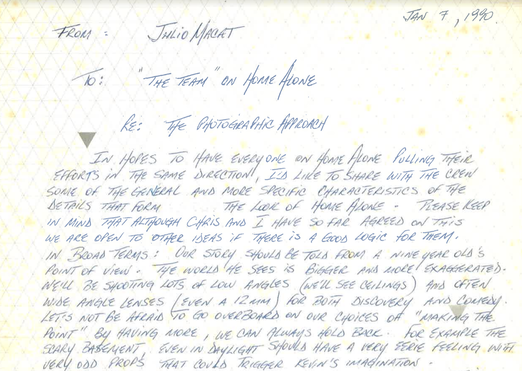

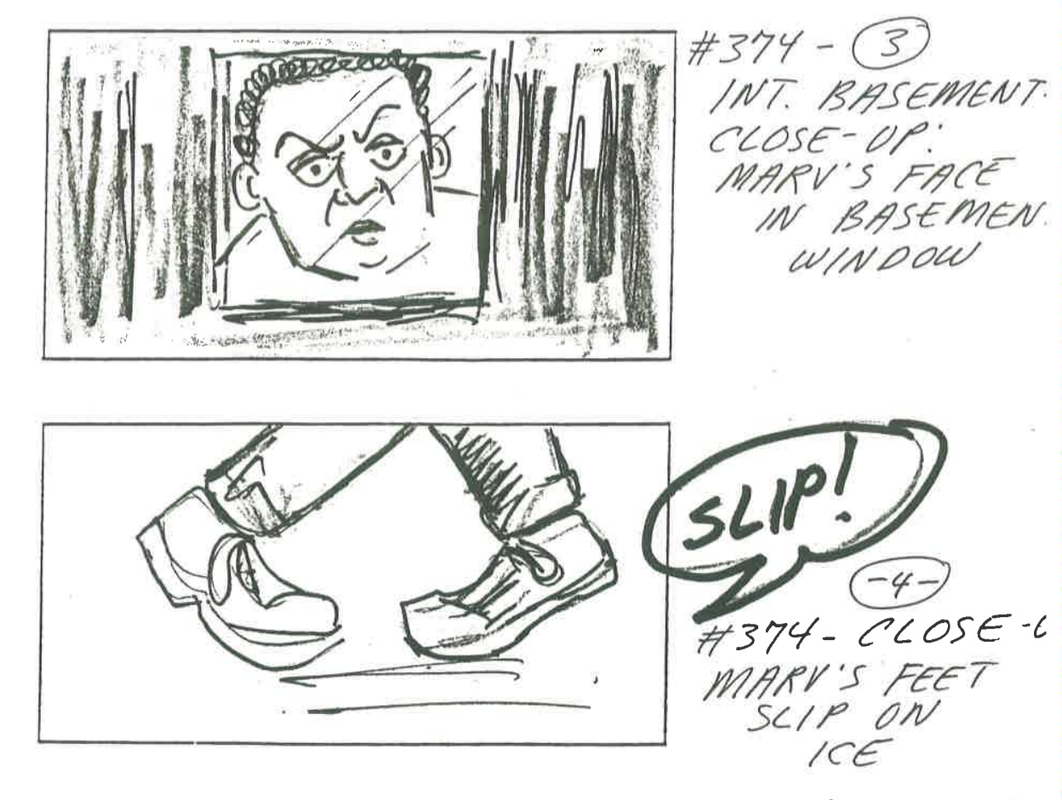

By Meg Moore Julio Macat breaks down filming stunts in Home Alone and how beginners should focus on their shots. Bridget interviews Julio Macat cinematographer and DP of Home Alone, Ace Ventura Pet Detective, and Pitch Perfect. “In our industry, the people who don’t survive are the people who are washing dishes with lukewarm water.” (on being passionate about cinematography Can you talk about your process of creating a visual design for any film and the relationship between a director or a DP? It’s so important and few people realize what a director of photography does. It’s a big title and sort of mysterious, but when you’re making a movie the basic elements are the script, then you have a director who theoretically will have a vision and an idea of what they’re going to do with that story, with that script, and then you have a specialist in photography who tries to be the therapist of the director and really draw out what they’re truly trying to say with the story. Often times a director will know what they want but they won’t realize it until they see it, and that’s where we come in. We bring in photography in order to tell the story. Photography for us as cinematographers is composed of three main elements. The composition side of it (the way you frame a picture), the movement of the camera; which helps convey the story – if you’re trying to convey a lonely moment you can have a little boy sitting at the end of a corridor and the camera slowly pulling back – and to your heart that says, “oh he’s alone”, and lighting which is arguably the most important because lighting sets the mood and it sets up a situation. If the story is about someone being very sad about to commit suicide, you wouldn’t have this happy lighting in that scene. You would convey it by having tones of light that are on the cooler side or misty. As cinematographers, we bring that to the party, then we hire a crew of about sixty people, lighting people, grip people, we oversee the art department, and I like to think of ourselves as the gatekeeper of the image. Literally there’s a gate in the camera and a picture is coming through the lens and we’re the last person who can say “hey do this, do that, fix that, tweak that” and try to get the image to be the best it can to tell the story. With Home Alone, there were times where the film was funny and light, but there were times where it was supposed to be scary too. When the kid goes down to the basement it’s supposed to be spooky, the house is supposed to scare him, and the main guy’s shadows on the walls and stuff like that. You have to ground the story you’re trying to tell with the photography, that’s what a director of photography does. What was your creative process for Home Alone ? It was my first movie that I ever photographed, that was sizable – I had done one other little horror film that nobody saw before that. I had done a job in what’s called a second unit to a bigger film because the director who liked me said, you do all the action photography to this specific film which was called Tango and Cash, and they liked what I was doing, so they thought oh, here’s and up and coming guy, I was almost 30. The studio which at the time was Warner Brothers said let’s put him together with this young director who had done a couple of films, Chris Columbus. They introduced us, and we hit it off, from that moment on it was about trying to do something special. It was a story for kids, we kept referencing other movies of what we wanted it to feel like. A Christmas Story was something that came up a lot, we wanted to do something that was entertaining and for the kids and have a vibe of the feeling of Christmas. So, we just hit off each other, and I showed him visuals that I really liked, and he liked those, so that’s how our creative process started. You have a script, you have a director that tells you what he’s trying to do, and then you bring stuff to the party that helps the director realize what he thinks he wants. The interesting thing about making movies is that you never really know what you’re going to get until you’re doing it. It kind of builds as it goes. What happened with home alone is that it was one of those convergences where every aspect of the movie helped the other aspect of the movie. It was a great script, it had a director with a vision, I brought the photography to the party, we had John Muntos who was a great production designer, and we were really fortunate to have Raja Gaznell who ended up directing movies afterward – he edited the movie, and then how lucky could we get that we get John Williams an iconic musician, used by Spielberg, to see a rough cut of the movie and loved it and came up with these tunes that were majestic and elevated everything. It was one of those cases where everyone was firing on all cylinders and everything just converged. What visual references did you use? I know in an interview you mentioned Spielberg and the crane shot. That whole church sequence was really inspired. We were filming in the church, but we were trying to do the shot of the outside of the church (it’s still one of my favorite shots I’ve ever done) and you always emulate – you don’t imitate. In photography, it’s weird, you can’t even imitate yourself. Sometimes you do a shot, and you have to come back the next day and do exactly the same shot, and it’s never exactly the same. There’s always these variables that change everything. So, a tip of the hat to Spielberg and all the wonderful shots that he’s ever done where the cameras down low – on a big beautiful shot and as the person walks away the camera slowly rises, that’s sort of a classic thing to do that’s proper for the moment. I think everybody is influenced by everybody else. Not to rip off things exactly because it’s never exact, but if you’re going to imitate someone imitate Spielberg.  Mission statement to the crew of Home Alone. Courtesy of Julio. Mission statement to the crew of Home Alone. Courtesy of Julio. When you shot Home Alone did you have a specific color palette you worked with? We did, it was so important to me because it was my first movie. I wanted to make sure that everyone in my crew was on board with the things that we had been talking about which is something you normally don’t do, but I was going by instinct – so I wanted my whole crew to know what our color choices were, what our influences where, so I wrote this two-page mission statement and I just wanted to get everyone excited about it. I haven’t done it since, but I think it’s a really good idea especially on a smaller production where it’s all about the heart and the passion for getting everyone on the same page. Obviously, the Christmas colors were important but also, we talked about the colors of when the family flies and goes to Paris, how that would be a different world. We used a lot more blues. From the minute, they land at the airport to the apartment they’re in. we went for a much cooler feel to separate the family in a cool environment and the boy in the very Christmassy reds and greens and golds. We stuck to it pretty well. When you start controlling color, and you start doing things a certain way – when a weird color comes into the mix, it stands out – like no this doesn’t belong. It’s something that once you start controlling, it takes a life of its own. John from Chicago asks about the scene where Kevin wakes up alone and sees flashes of his family members saying horrible things to him, it looks like the actors were saying the lines directly to the camera. How and when were the shots conducted since it clearly wasn’t part of the original scene? It was in the script. It was in his imagination. What’s interesting is that 30 years ago when we did this visual effect were not as great as they are now, so everything has sort of a milky feel to it, and that’s because the visual effects dissolves they would do were not as good but they kind of worked to the favor of the fact that it was kind of dreamy-ish and felt it like a memory so we kind of went with it instead of worrying that they were kind of shitty visual effects. That goes to show you that sometimes you land on accidents that work. It was definitely shot during the movie, we wanted to distort it because to me and the director when you think of a memory it’s never clear. It’s sort of distorted, so we used distorted lenses. It was a 14-mm lens and the lighting was cooler and slightly different from the rest of the movie. Everyone was going over the top because of the idea that a kid remembers things in an amplified way. It was an over-the-top memory and that’s how we approached it visually. He’s sitting at the table and he remembers all of this and then he shifts from being afraid to being like “hey I’m alone, screw my family” and you see it in his face shift over. From there he’s happy to be by himself and jumps on the bed. Mariah from Texas asks, because there were no Go-Pros back then, how did you film the POV shots of Kevin sliding down the stairs? I found a tiny camera the size of this (holds up a newer Polaroid camera), and it was an Ari2c camera, they made a body that was tiny that they used for medical purposes, they call it the medical 2C camera, and it had a short spool, a 100 ft spool which was less than a minute. The magazine was tiny, and we used to call it bonus cam. I call it the chicken shit camera because I was so scared when we started, it was my first movie and I wanted to make sure that we got everything. We had two cameras rolling most of the time, and then we had bonus cam which was this tiny little camera which I had gotten used to using from doing stunts. I would place it close to the car driving by and interesting spots where you couldn’t really put a camera, but you could put bonus cam and then plug it into a battery, and it would just roll and get whatever it got. It was usually a good cut for an action sequence. When we started doing stunts I had bonus cam and I started putting in a place where I was afraid that something would happen in decent, and I wouldn’t catch it because both cameras would miss it. So, I would use the bonus cam as a wide and stupid shot of the thing. Just to have it, and make sure we didn’t miss it. At first, we put it on a stick and would fly it over like a boom microphone and just have an aerial which was usually a 16 mm lens. Or when Peschi was going to fall on the ground we’d just put it wherever we could and accidentally great things were starting to happen. Peschi would fall right in front of the lens or near it, and because it was so little no one even knew the camera was there. We started to see at dailies that bonus cam was getting some really cool shit. We were like oh my God bonus cam is cool! We love these shots, so then we started to think, what else can we do with bonus cam that’s kind of nutty and fun? We put it on a rope and would throw it down things, like when the iron come down. We threw bonus cam down on the rope and that became the point of view of the iron hitting him. Bonus cam became the star of the show, and we started to think about where to put our “go-pro”. Bonus cam helped to design a style of the things we were doing of big and wide and close and then translate it to other things we were doing, including the boy running up to the camera and going ahhhhhh and running away. Those were because we saw our “go-pro” was working and we started using it as a stylistic piece of what we were doing. Have you used that bonus cam on other shoots? Absolutely, when you learn something like that, any time there’s a stunt that’s going to happen, for me there’s a bonus cam somewhere. It draws you into the action.  BTS of Home Alone filming outside. Courtesy of Julio. BTS of Home Alone filming outside. Courtesy of Julio. Steve from Australia wants to know what challenges did you face filming Home Alone? Was snow a problem or was it all fake snow? Snow was a problem, but like any problem you try to take it to your advantage. The very first day of filming we shot a sequence where the boy goes into the pharmacy, and he gets a toothbrush and the old man comes in, and he runs away. WE shot that whole sequence when there was a massive snowstorm outside to the point where we laid our cables and then the snow storm came in, and we couldn’t find our cables. There was a foot and a half of snow, it was crazy we had to leave the stuff behind. There was snow when we didn’t want it sometimes, but we adjusted to it, but after the big snow fall we went ahead to do the big day exteriors where we needed the snow outside, and then we couldn’t get all of our work – so when we had to continue doing those exteriors we had a machine that’s like a tree chipper, and you throw blocks of ice in it, and it shoots out little bits of ice that look like snow, so in the foreground of the scene we had real ice chipped snow and in the background of the scene we had potato flaked snow. Which is fake mashed potatoes that they blow and looks like snow. We also used foam, which looks like snow, but when the wind comes up in Chicago, we had these bubbles blowing through the shot which is ridiculous. Those were the three different types of snow. When we did the church sequence, which is my favorite sequence in the movie, it had been snowing, and I remember going to the church, and we were all waiting for the snow to stop. I remember saying a little prayer, I remember talking to the priest he was excited that we were filming at the Trinity Church, and he may or may not have given me a glass of wine, but we won’t get into that. We walked out, and the snow stopped. The first AD said we have Jesus on our side! The snow stopped and we shot it. It was a magical moment. That’s where film Karma comes in, for all the good things you’ve done in the past, you get thrown a bone, you get the right cloud, you get snow stopping, things like that. If you had to choose only one lens to use for the rest of your life, what would it be and why? Either a 35mm or a 32mm. You’d have to think about the story, you know one’s a little bit wider and a lot of people think, including Hitchcock, when you go like this (cups hands on the side of face) and you look out, and you’re trying to see something that’s very much what your eyesight is seeing without distortion, a lot of people think the 35 is that milliliter. When Kubrick used to shoot location photographs, he would insist that all of the shots be done with a 35 mm at a certain height, I think it was 8 feet. So, you had to be on a ladder with a 35 so as to not distort the location, so you can judge it just for what it is. It’s a lens that can work for a close up, and it can also be far enough back and work for a wide shot. I’m not sure 100%, but you know the movie 1917 which used pretty much one lens, it was a version of a 35 mm, and spherical, but they shot it in a 4k format, so it was close. It was close to a 35. I don’t want to say in spherical it would probably be around a 29 mm. What my friend Roger Decans shot that film with. Do you have any advice for beginner DP’s? If you’re calling yourself a DP, somewhere on that path to where you are now, you photographed something that really made your soul come to life, you did a photograph or a picture or a moving image and went “oh my god I love this”. It’s the equivalent of in the old days where you take a roll of film you shoot all these pictures, you didn’t know exactly what you got, you took it to get processed, it came back, you looked at it and there were three great surprises. Three photos that make you go “oh my god, I can’t believe I photographed this! I shot this, these are good”. That feeling that you get of accomplishment and excitement, and the fact that you captured a moment that’s passionate that says something and that made you glow, this is why you’re a cinematographer. My advice is to try not to lose that. I’ve worked with a lot of first time directors and young cinematographers, who ask me, and I always say, “you can do a lot of shots for a scene. You can do Steadicam , 360, you can run around, but if you had to tell the story and pick one shot, one millimeter, one position, if you had to tell that story in one angle, what would that be?” It’s an interesting exercise because you’re going to be in one place and often times you want to be in that place at the beginning of the scene and at the end of the scene there’s a better place to be in, but often times you want to pick the place that tells the story in one shot, and that’s the master shot. When you pick that spot, it just makes it all work. You’ve succeeded in transforming that passionate moment you had interpreting the story into a visual. That would be my biggest advice, to not lose track of the one shot that tells a story, and be passionate about it. Do ordinary things in an extraordinary way. That same shot could be as simple as a door is open and people far away are talking, and you’re seeing it from this perspective and that could be a shot that tells a story, or, there could be a keyhole, and you make a bigger keyhole, and you put your camera through it, and that’s looking at the scene in the other room. It’s a similar shot, but it’s two completely different things. The real fun of being a cinematographer is picking those little things that changes the way you tell a story. That’s the exciting thing about what we do. A lot of it can be technical, there can be a lot of time and energy thinking about what camera you’re going to use, what lens, and that’s all well and good, but in the end, it doesn’t really matter. You can shoot it with your i-phone. What matters is the shot that you’ve created that tells the story. Rather than get crazed with resolution, 2k, 4k, it’s the shot that matters, and it’s what makes us special in storytelling. Don’t lose track of that passion that makes you make that one shot. You want to have something that feels professional, I understand that but it’s amazing that Canon makes these SLR type cameras that really do look professional, but be guided not by the equipment, the equipment is just there to record. I worked with Antonio Banderas one time, he directed his first movie called Crazy in Alabama, which is another one of my favorite things that I’ve photographed, he’s a very passionate guy. I remember one time we were doing a scene and things were late, and they didn’t have the right items and there was chaos on the set – which happens a lot on student sets, I’ve witnessed it, everyone’s running around with their heads cut off and everyone’s a director. So we do this and then “roll the camera roll the camera!” and you mark it, and then there’s a silence, and then the scene happens, and then maybe some magic happens, and we cut and Antonio comes over, and he says to me in broken English, “Aren’t you glad that the camera doesn’t have any feelings?” and I looked at him and go “what do you mean?” and he goes “yeah it’s crazy, it’s insane up there, all kinds of hell is breaking lose but the camera just records what’s on the frame, it’s not affected by the fact that everyone’s in a bad mood, it just registers it”. It’s interesting that often times you can just have your recorder guided into what you really want to do and not the madness of everything else that’s going on outside of it. That’s why it’s really important for us as cinematographers to feel like the gatekeepers. The keepers of the image. There to make sure there’s not a tag in the wardrobe or an imperfection in the makeup that’s terrible, we’re there for that and that’s our responsibility. That everybody’s job, the costumes and props, everything is ruined unless the keeper of the image says hey hey hey look at that, is that what we want? Without embarrassing anybody, but things happen on a film set. That a fun part of it. The pandemic has impacted a lot of the film industry, set protocols, movie theaters being shut down, streaming, and everything else, what do you think the future of filmmaking is? Being on a film set, you’re always adapting. You’re always changing to get to the other side of the problem, we’re problem solvers by nature. Of course, we’re going to figure out if everyone’s wearing masks and everybody’s testing we should be able to get back on set and be safe. We’re safe when we’re doing stunts, were safe when there’s 20 gallons of gasoline and there’s going to be a tremendous explosion, and you have four cameras in the vicinity of it you’re going to figure out how not to kill people – so it makes sense that we would be smart enough to try to get around it. I’ve had three different projects fall apart unfortunately because of COVID-19 and it’s sad, but we will come back to normal eventually. I’m dying to get back to the theater and see something as it was meant to be seen, on a big screen. I hope that people don’t forget that experience, because when we’re making a movie we’re creating the experience not to sit at a monitor or a little screen – it’s not the experience that we love sitting in a movie theater. We’ll get back to it in a year or so. We have to shoot for that though. We can’t all of a sudden become these Quibi people that are going to watch our work on a cell phone. I hate that, an image is meant to be projected, and meant to be shown in all its glory. Everyone’s effort from the wardrobe to the makeup to the hair stylists to the set design, all of it is appreciated on a big screen. We shouldn’t lose strike of it, and we’ll get back to that, but it’s going to take some time. What’s next for you? I don’t know, I’m reading a script now, and it’s possible, we’ll see. I don’t want to jinx it. It could happen in March – I’m kind of gun shy because I prepared three movies and then the week before, one of them the actor didn’t want to commit to it because of COVID-19, the other one it came to the conclusion that it was too expensive to do all the proper COVID-19 testing and the budget couldn’t accommodate it, and so I’m open. Maybe you guys will write something amazing and send it to me. Anything is possible, shoot high. You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression. If you’re going to send a script to someone make sure it’s the very best script you can write. That person could say, yeah I’ll read it. It’s got to be good because that’s your shot. MY other recommendation to other filmmakers is before you roll that camera before you finish your project, ask yourself “have I done everything I could possibly do to make this something that excites me or that I would want to go see?”. Don’t just do it as an assignment, do it as if it means everything, because it does. If you want to be in our industry, the people who don’t survive are the people who are washing dishes with lukewarm water. It’s the people who have to work with hot water – you want to go for it, you want to make a statement. You want to make it count you want people to remember your work, so it shouldn’t be half assed, it should be the very best you can possibly do. The beauty of this industry is you have 100 years of history of amazing movies, you could go back to every movie that won the Oscar for the next 50 years and really from those there’s something that’s going to speak to you. Whichever movie you picked, there’s a reason why you loved it and there’s a reason why that may have something to do with your taste and developing your taste. If you love that, maybe do your version of that. Look at all the great stuff we have as background research. The American Society of Cinematographers is 100 years old. 100 years ago some dude figured out that you can pass film quickly through a gate and get an image and here we are trying to do the same thing. Well it better be a good picture, somebody worked their ass off to figure out how to make movies. Set your sights high on your projects and I think that we’re all storytellers and the more that you’re influenced and the more passionate you are at telling your story the more that you’ll be guided in the right direction.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorBridget Johnson is the president and co-founder of Dare to Dream Productions. She writes and directs thought-provoking films that inspire others to follow their dreams. Archives

March 2021

Categories and authors

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed